“Gone are the days when you walked through the door…”

“Gone are the days when you walked through the door…”

In the last few years there’s been plenty written about Shack. Liverpool’s great-lost band, hampered through misfortune and tragic mishap. They’re the stuff of muso-pub banter legend. The unfulfilled promise of the Head brothers has proven irresistible to music journalists, seduced by this Liverpool 4-piece possessing that oh-so-rare mix of kitchen-sink grit and heart-breaking vision. On the back of this, they signed to Oasis’ record label, put out a “Best Of…”, even had a documentary made that you can see online.

But back in 1996, before You Tube and My Space and everything else we’ve now got on cyber-tap, I was sixteen and soaked in sound, and Shack seemed pretty much unheard of. I’d occasionally find a few long-toothed hacks and die-harders from Liverpool who could remember their 80s synth-heavy Ian Broudie produced debut “Zilch”, or the earlier incarnation from the Head brothers, The Pale Fountains. Music was everything to me in those days, dissecting records, always on the lookout, prowling through second-hand shops and record fairs for elusive 12-inches. On Mondays, you’d find me after school in Our Price scanning through the latest singles or bussing up to buy the new 45 from Berwick Street. Wednesdays were special – NME came out. Without fail, I’d be in the canteen at lunchtime immersed. “Cool Britannia” was upon us – New Labour, new sounds. Noel Gallagher shaking hands with Tony Blair at number 10. Damian Hirst and Tracy Emin doing their respective things. Style came before substance, it suddenly became fashionable to be from England, and to have something to say, even if you weren’t 100% what it was you were saying. There were reams of these new bands, most shit, a few shockingly, and even fewer decent. Playing live on TFI Friday seemed to be the credentials that made each of these groups, and looking back, most didn’t really get beyond that footnote status.

But that was cool. They were great times. I was learning to write and play myself, learning to listen too. After the shoe-gazing post-baggy hangover from the early 90s, there seemed to be a freshness and simplicity to what I was hearing. I liked the vision of the bands like Cast or Oasis, even if the actual songs lacked the depth that demanded repeat listens: “I’m gonna fly, up in the sky, so very high, yeah-yeah-yeah!”

I was starting to dig out the bands that the bands I liked were in to. The Byrds, Love, Happy Mondays, My Bloody Valentine, The La’s, The Roses. I knew there was stuff out there waiting to be discovered, like I was on a sonic adventure without knowing what I was looking for.

One day in March, I’d picked up a copy of VOX Magazine, the NME-monthly. Bjork on the front cover looking weird, Trainspotting being touted as “Film of the Year Already!” And in the album reviews section, I came upon a review by John Mulvey for “Waterpistol”, Shack”s second recorded album. I reckon I’ve read this review over a hundred times. I read:

“It recreates the moment when frayed acoustics go spiralling off into psychedelia”

The history of the record is a pretty sad tale, I’d soon discover. The studio containing the master tapes burnt down, and producer Chris Allison disappeared to the States with the only DAT copy. Four years on, tiny German indie Marina came in to save “Waterpistol” from the dust it was gathering and put it out, by which point, the band had dissolved in a wave of disillusion and addiction. Sounded good in writing, but would it stand up?

So I toddled off to HMV on Oxford Street that weekend and found a copy in the upstairs section, not having much of a clue what to expect. Putting on that CD was like one of those rare moments where I had no preconceptions. No one had ever heard of Shack. It could have been rubbish, a waste of thirteen quid and a bus to town. But instead, what I got when I played that album in my Mum’s kitchen that Saturday is an irreversible moment. Like my first kiss, my first getting dumped, my one and only heart shattering from the girl I was meant to be with. Things would never be quite the same.

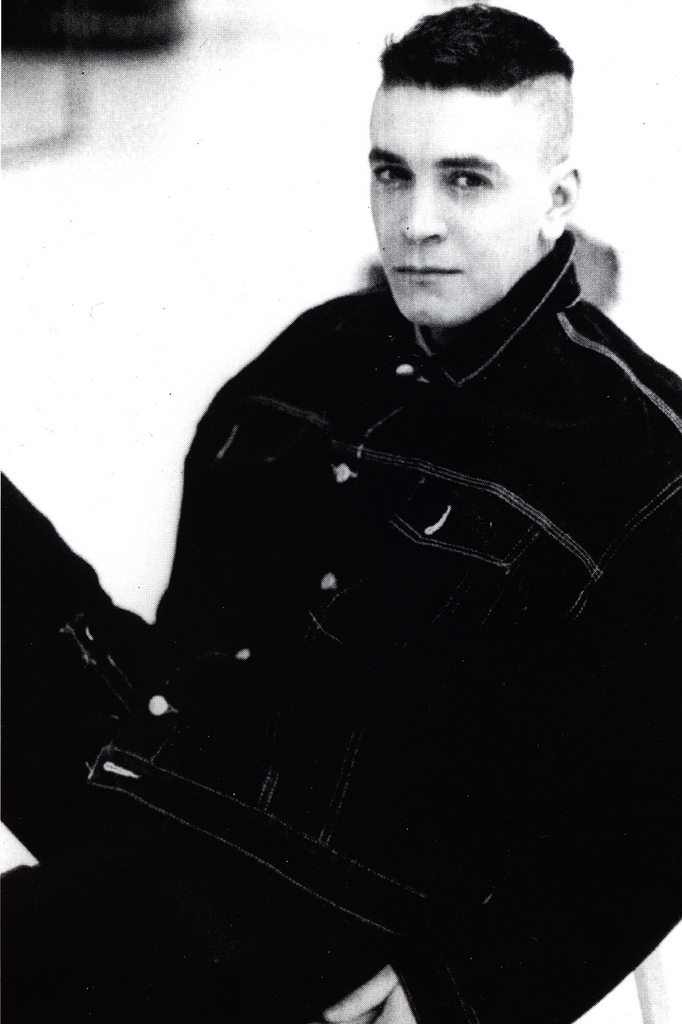

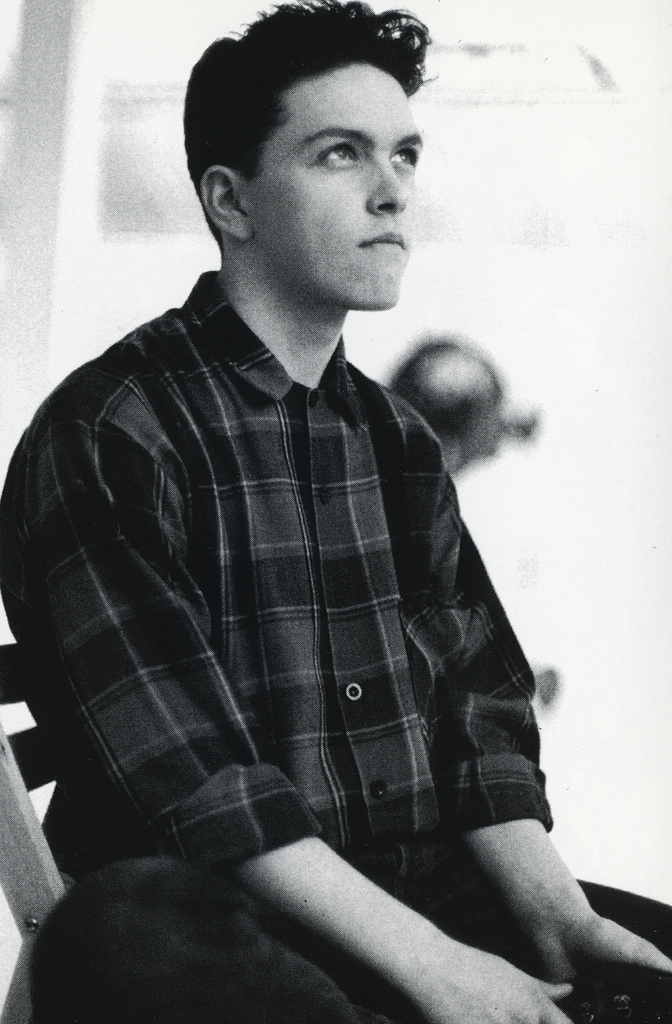

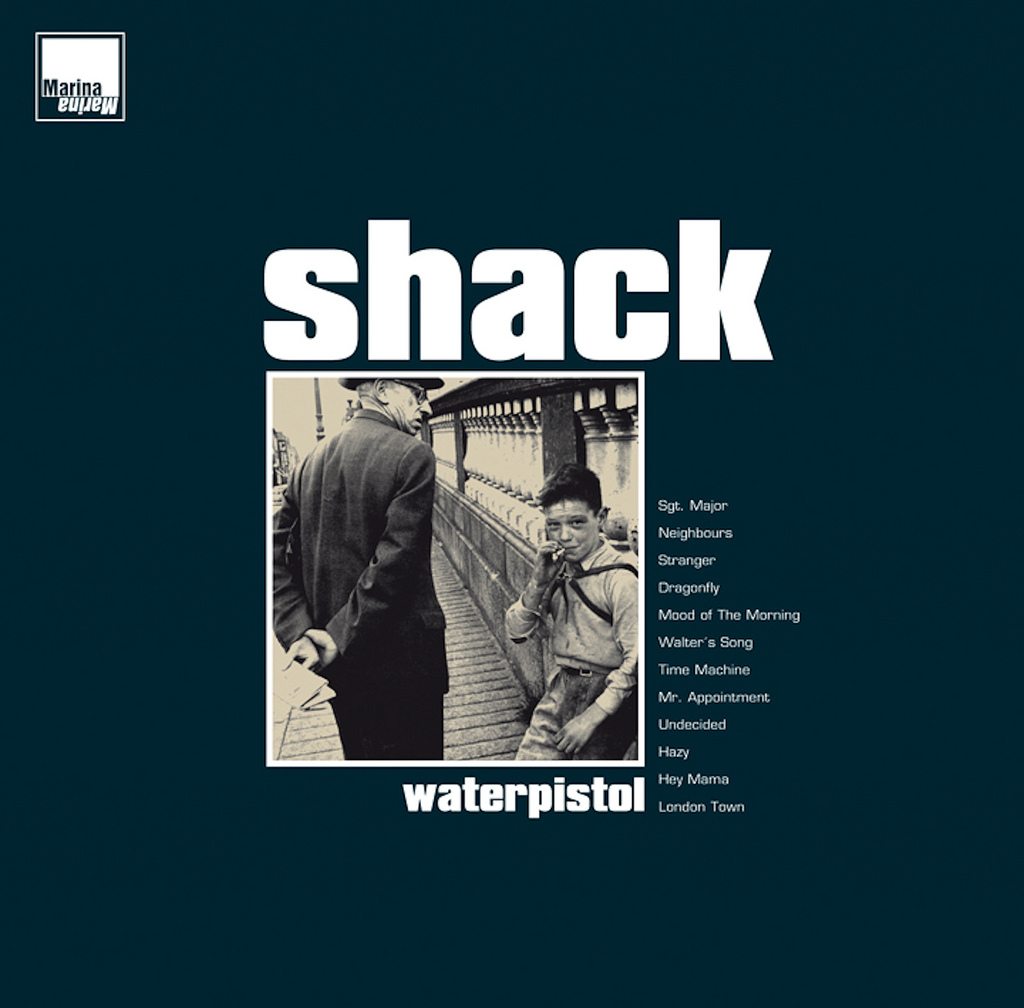

The sleeve is reminiscent of The Smiths’ period nostalgia covers, a black and white Bert Hardy-esque snap taken on a bridge. We see a scruffy kid with shorts and a satchel tugging cheekily on a fag and grinning at the photographer, blissfully unperturbed by a suited bespectacled businessman strolling past, with pomp and contempt all over his face. It’s a great image. A captured moment, where rough meets smooth, not needing any explanation. No pictures of the band, instrument-clad and painfully hip. Inside the sleeve, more clues were found. Two guys, who I later learnt were brothers Mick and John, singer and guitarist respectively, and the driving force behind Shack in all their various guises. The photo of Mick really struck me – I saw in his eyes something I had to know, as if he’d seen things I hadn’t, as if he’d survived the poisonous heartbreak that only the true English Rose tastes. There he sits, cool-as-fuck, collar popped and military crop, staring with faint amusement at the camera, and straight at me. “Eyes that know” I would go on to say to those deserving folk I shared the album with. Most thought I was being a little weird, and should maybe lighten-up. But fuck it, I thought. I had to know what those eyes knew.

“Sgt. Major” is the opener, an effortless statement of E’d up ambition. This could’ve stood up to anything by the Mondays or Roses for its instantaneousness. A lazy drum intro hooks us in before we’re swirled and seduced by the twangy 7th chord and loose bass groove. It’s poppy without being twee, cocksure without being arrogant. But it was the voice that stood out for me the most:

“Sgt. Major” is the opener, an effortless statement of E’d up ambition. This could’ve stood up to anything by the Mondays or Roses for its instantaneousness. A lazy drum intro hooks us in before we’re swirled and seduced by the twangy 7th chord and loose bass groove. It’s poppy without being twee, cocksure without being arrogant. But it was the voice that stood out for me the most:

“You could be the Sgt. Major, if you really want to.”

I’d been used to hearing nasal barbed-wire vocals up until then, white boys swerving the idea of soul out of fear of losing face, but in Mick Head, here was a gruff Scouser who sounded like he’d had the arrogance beaten out of him, with nothing to lose but tell the truth.

“Neighbours” follows, an edgier affair, climbing walls with cabin fever, TV on with the sound turned down, huddled round bus stops and phone boxes in the drizzle and cold. It gave a hint to the band’s darker and self-destructive side, which went on to nearly get the better of them. In the mid-section, Mick gives a desperate cry, followed on by a Scouse voice narrating low in the mix. The words are muffled amongst John Head’s icy guitar teardrops, but at one point you can make out the lines “There’s only one way out, like…” before it crashes into the chorus again.

“Stranger” continues the melancholy, but where as “Neighbours” hinted at urban desperation, here we have a jazzy waltz, reminiscent of “Moon Dance” by Van Morrison, characterised with this other-worldly Baroque feel. It bobs and sways into different keys and rhythms, lush and smoky psychedelia that carries a vague and haunting quality, stripped down to its bare essentials. It makes me think of horse-drawn carts trundling across baron moors and dales late into the night.

“Dragonfly” is a wake-up, this straight-ahead piece of semi-acoustic pop-psych, complete with surf guitar licks and Mother Nature lyrics. But whereas as piles of “Cosmic Scallies” past and present have written vague 2-dimensional tunes that are catchy enough, but lacking the originality and whit of “Paperback Writer” or “There She Goes”, with a song like “Dragonfly” there’s the ingredients for it to shine on first listen but still stand up time and again.

“Mood of the Morning” continues, and was like nothing I’d heard before or since, deceptively simple, yet at the same time, so rich with colour, humour and honesty. It was as if Mick Head had discarded all the synths and pretence, and was pulling from a different source, to reach for this undeniable truth. Perhaps more than any other song off the LP, “Mood…” encapsulates his ability to intuitively not let his ego get in the way of the song-writing. A 2-chord acoustic strum, meshed with DIY bongos and scrappy things, and then Mick singing about a girl who loves The Mondays and will dance to keep the evening going no matter what. It’s got this Summer-breeze innocence that’s irresistible, and his voice still sounds mega to this day. Near the end, the tone becomes tinged with sadness and reflection, layered harmonies hinting towards that sinking you get when you realise the party’s finally over:

“Mood of the Morning” continues, and was like nothing I’d heard before or since, deceptively simple, yet at the same time, so rich with colour, humour and honesty. It was as if Mick Head had discarded all the synths and pretence, and was pulling from a different source, to reach for this undeniable truth. Perhaps more than any other song off the LP, “Mood…” encapsulates his ability to intuitively not let his ego get in the way of the song-writing. A 2-chord acoustic strum, meshed with DIY bongos and scrappy things, and then Mick singing about a girl who loves The Mondays and will dance to keep the evening going no matter what. It’s got this Summer-breeze innocence that’s irresistible, and his voice still sounds mega to this day. Near the end, the tone becomes tinged with sadness and reflection, layered harmonies hinting towards that sinking you get when you realise the party’s finally over:

“When she’s gone, it’s like nobody’s there, empty eyes, empty stares…”

When I first heard it, I knew. That might sound silly, but that’s how it was. Things fell into place. John Mulvey’s claim in the VOX article, that this sounded like “…some of the most outstanding, honest music that’s been made this decade…” didn’t sound bold at all. I was convinced.

Understand, I fancied myself as a romantic back then. I took myself very seriously. And lyrics and sounds like this…well. They woke me up. So real. Mick Head had appeared from nowhere, a complete stranger from a place up in the North, but he knew the unwritten verses from my heart. And so it goes…

“Walter’s Song” gives an affectionate nod to “Night of the Hunter”, the eerie Robert Mitchum thriller about a knuckle-tattooed child-stalker. There’s loads of weird and subtle references to music and cinema throughout “Waterpistol” like this. But whereas Shack’s contemporaries tend to make clunky attempts to re-hash standard-fare influences, with the Heads there’s intelligence there, a sense of admiration rather than imitation. Not to mention a pretty wide knowledge for some far-out stuff I’d never heard of. “Walter’s…” is carried by a lullaby melody, lifted from the dreamy interlude in the film that I went on to discover on the back on the song, and Mick’s husky voice has never sounded better. It’s the kind of brave and weird move that your typical Brit-Pop dazzlers would’ve literally taken decades to come up with.

Mid-way through the LP, “Time Machine” would’ve made the best single in my opinion, a lazy waltz-time piece, complete with twisting key signatures, peaks and troughs, rising to an effects drenched technicolor crescendo. A warm nostalgia trip, thick with whiskey, whim and good-humoured regret.

“Mr Appointment” tells the story of a round-the-clock dealer on the run, with “Ticket to Ride” stop-start drumbeat and a siren guitar lick over Mick’s acoustic bashes. The song pushes forward towards the 6-minute mark, complete with crashes-a-plenty and “na, na, na”s…”, never letting up until the closing few seconds where it collapses into a dead-heat, and Mick cites his Beatles heritage with a police-siren “Day In The Life” lifted-vocal: “D’you read the news today, oh boy…” before the whole thing spirals down the plug-hole some more.

“Undecided” is track 9, an achingly blue semi-acoustic, sounding like it could have been written anytime in the last few hundred years. A simple, 4-chord repeat, with Mick and John’s harmonies never letting up. It recreates the pain of being pulled two ways and the things we resort to when indecision gets too hard to bear:

“It’s gotta be like sticking a needle in your arm when your sleepin’ and then you could be somebody…”

“Hazy” arrives with a train-track “chukka-chukka” groove that steams ahead into Hansel & Gretel tale, with characters like Michael and Siobhan who drink tea and pass cheeky grins when no one’s looking. I liked to think it could’ve been lifted from some dusty folklore book that Mick picked up on the Portobello Road. It shuffles through verse and chorus, then jars suddenly into a moment of fleeting doubt, with Mick bowing his head and almost whispering:

“Hazy” arrives with a train-track “chukka-chukka” groove that steams ahead into Hansel & Gretel tale, with characters like Michael and Siobhan who drink tea and pass cheeky grins when no one’s looking. I liked to think it could’ve been lifted from some dusty folklore book that Mick picked up on the Portobello Road. It shuffles through verse and chorus, then jars suddenly into a moment of fleeting doubt, with Mick bowing his head and almost whispering:

“What was that thing that you done? How can you dream without loneliness?”

It’s a disarming and daring shift. We hear the sound of thunder and rain, and are reminded that the light-headed rush of Summer must always come to pass.

“Hey Mama” is the penultimate piece, a little like “The End” by The Doors. Middle-Eastern guitars and a 2-chord guitar and drums heartbeat collage into a wrenching call for maternal safety. Mick’s voice carries a desperation which I’ve not heard matched. Believe me, I’ve spent countless late-nights, smoking roll-ups and listening to those haunting words:

“I used to think that falling was a game…”

Gets me every time.

“Waterpistol” winds down with “London Town”, a bittersweet snippet of stripped down acoustics, with the similar Elizabethan sizing that seems to characterise the LP. It’s a story about coming to the big city for the first time, the highs, lows, humour and the run-ins that follow. Buying indigestion pills that look like E’s, calling up pals in a flap, then coming-to, and seeing tomorrow begin to dawn, and everything begins to get clearer again through the fog.

It’s a lovely, romantic way to close the album, tinged with a little sadness too. We’re left with a suspended chord, and the distant sound of a car whoosh by, leaving a sense of heady and calm contemplation on what’s to be done.

And then it’s over. 12 songs. Just under an hour’s worth of music, that very nearly never got heard. Thinking this through, I guess what does it for me is the way “Waterpistol” has this knack of sounding utterly contemporary, whilst it still drawing from the past. When I listen to it, I’m hearing sun-drenched West-Coast psychedelia played on battered acoustics in some Liverpudlian housing estate kitchen. It’s Ken Loach meets Arthur Lee. But whereas so many of the Brit bands before and after “Waterpistol” seemed to lose themselves somewhere trying to duplicate a sound in their heads that they thought people would like because it’s gone down well before, with Mick Head, and “Waterpistol” above all his others, it’s the honesty of the songs that makes it stand up to be heard. No airs or graces. No Rolls Royces in the swimming pool, TVs flying from the Columbia Hotel windows or any of that bollocks. These 12 songs cut through all the trite, and just deliver.

I’m thinking how this may all sound a bit sentimental – but sod it. I’ve grown up with these songs. I’ve fallen in love, fallen on my knees, fallen into hard times and picked myself back up again, always with a soundtrack of “Waterpistol” never far away. I played it the other day, start to finish, and got this wave of familiarity, too many memories to make sense of, instead more like this tug of emotion, like I’d been reunited with my best friend. Sounds good to me. I’ve met a lot of people who’ve come and gone since. Fair-weather friends. But with “Waterpistol”, it’s a different affair. We’ll know each other forever. Deffo.

– Elliot Sweeney

Thanks to Stefan Kassel for the hi-res cover scan

8 Comments